This year, ASEAN, which consists of 10 countries in Southeast Asia, i.e. Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Brunei Darussalam, Vietnam, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Cambodia, is 54 years old. ASEAN was formed on August 8, 1967 in Bangkok, Thailand which was represented by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Indonesia (Adam Malik), Malaysia (Tun Abdul Razak), the Philippines (Narciso Ramos), Singapore’s Minister of Foreign Affairs (S. Rajaratnam), and Thailand (Thanat Khoman). In that day they signed the ASEAN Declaration, or better known as the Bangkok Declaration.

In the Bangkok Declaration, the objectives of the establishment of ASEAN are listed. Probably the main or initial goal of the establishment of this regional organisation was to create peace, security, stability and prosperity in the Southeast Asian region. This was motivated by the current regional political condition in Southeast Asia in the 1960s which was prone to conflict due to the influence of other countries’ ideologies. At that time the cold war between the Soviet Union and its allies and the United States and its allies was in its peak and the Vietnam war was raging. At that time, leaders from countries in Southeast Asia believed that if conflicts between countries based on ideology were allowed to happen or continue, they could disrupt regional stability which could hinder development. The fear of the “domino” theory of the Vietnam war at that time was very real especially for the Suharto government in Indonesia because a year earlier the country was shaken surprisingly by a failed coup carried out by a group of military officers and backed up by the Indonesian communist party, an event known as the “G-30-S”. Since that incident, the Indonesian government and people have been very afraid and resentful of the communist.

So, without doubt, it can be said that at first, the main objective of establishing ASEAN was more of a non-economic in nature. Obviously, this is different from the main goal of the European Economic Community (EEC) formation, which was born as a result of the 1958 Rome Agreement which later changed to the European Union (EU) based on the 1992 Maastrict agreement. Since its inception, the EEC was fully economic motivated, although of course there was hope that with close economic cooperation between countries in West Europe, peace at last in the region could be realized so that no wars anymore.

Now the question: what is the future of ASEAN? This question is very important considering that in that time ASEAN was formed in a different world economic and political condition, namely there was the cold war, and the world economy was still very disintegrated. Whereas now it has changed 180 degrees: the cold war is long gone (communism is no longer something to be feared or hostile to) and more importantly because of technology advances the world economy has been highly integrated through trade, investment and the sharing of production processes between countries (known as global or regional supply chains). So, indeed ASEAN really needs to keep making adjustments to the changing world.

The following three main challenges are being faced by ASEAN. The success of ASEAN in facing these challenges will determine the benefits of the existence of this regional organization for the people of Southeast Asia in particular and the world in general.

Intra ASEAN Trade & Investment

The first challenge is to create trade and investment between member countries. It is stated that the objectives of establishing ASEAN are, among others: (i) to promote active cooperation and mutual assistance in the economic, social, cultural, technological and administrative fields; (ii) cooperate more effectively to achieve greater efficiency in the fields of agriculture, industry, and trade development including improvement of transportation and communication facilities and improving people’s living standards; and (iii) accelerate economic growth, social progress and cultural development in the region of Southeast Asian countries.

In this respect the challenge facing ASEAN is how to improve export-import and investment flows between member countries. Ideally, trade and investment within ASEAN (intra ASEAN trade & investment) should be greater than trade and investment between ASEAN and the rest of the world (extra ASEAN trade & investment). However, based on data from the ASEAN STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2020, during the period 2010-2019 the average extra ASEAN trade is still above 70 percent of its total trade. In 2019, intra- ASEAN trade in goods was recorded at 632,604.3 million US$, while extra ASEAN trade in goods was 2,183,827.7 million US$. Less share of intra trade in ASEAN total trade is no surprise or not difficult to understand given the fact that many goods that are needed daily by the people and industries in member countries are not produced by themselves, or if they produced well but such goods are not really needed internally. So, ASEAN continues to depend on imports and exports from abroad.

The same happens with Asia-African developing countries. Their internal trade and investment are still much less than their trade with developed countries including Europe, US, Japan and South Korea. Specifically for Indonesia, African market is still “faraway” to reach.

The 10 ASEAN Countries

Myanmar Political Crisis

A new chapter of the political crisis in Myanmar occurred with the coup and the arrest of civilian leaders by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Myanmar’s military chief. Civilian leaders such as Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint were arrested in raids that took place in the early hours of February 2021. Their arrests took place before parliament convenes its inaugural, post-election in November 2020.

ASEAN could not do much other than hold a meeting of ASEAN leaders including Senior General Min Aung Hlaing in April 2021 that produced a consensus. It consists of 5 points of agreement: (i) an immediate cessation of violence in Myanmar; (ii) the need for constructive dialogue towards a peaceful solution, (iii) the appointment of a special envoy as a dialogue mediator, (iv) humanitarian assistance, and (v) the visit of the ASEAN special envoy and delegation to Myanmar. However, as of this writing, there has been no progress.

Indeed, ASEAN cannot do much because one of the agreements in the Bangkok Declaration is not to interfere in the internal affairs of other member countries. In principle this is not wrong. Ideally, each country should take care of its own affairs, not interfere in the affairs of other countries. However, in the current era of globalization and free trade where the world is increasingly integrated, it is impossible to apply this principle of “doing your own business”. Because problems in a country if not handled properly can have a negative effect on neighbouring countries. Some years ago, the forest in Riau Sumatra in Indonesia burned heavily and the smoke covered the air above Singapore and Kuala Lumpur. Air flights in both cities were disrupted. In this case, can the Indonesian government say to the Singaporean or Malaysian governments not to interfere while both countries bear the brunt of Indonesia’s mistakes?

ASEAN should be grateful that Rohingya refugees have not flooded into Thailand or other nearby ASEAN countries such as Malaysia and Aceh area at the western end of Indonesia. Perhaps ASEAN will say: “thank goodness there is Bangladesh”. In today’s era, economic problems (poverty and unemployment), social and political problems (discrimination, coup d’etat, certain ethnic oppression, civil war) in a country will immediately trouble neighbouring countries through the flow of refugees. This regional or international refugee problem was not yet so popular in the 1960s when ASEAN was formed. But now this is a potential problem that ASEAN will face in the near future, not necessary from outside the region but can happen also inside ASEAN: the Myanmar case is the actual example.

Frankly, it seems that ASEAN has no choice but to review the point of their agreement that prohibits member countries from taking care of problems in other member countries. There are two types of intervention, namely negative and positive. A negative interference is what the United States government alleged that the Russian government has interfered in the 2016 presidential election. Meanwhile, what ASEAN needs to do is a positive intervention. In fact, the ASEAN consensus in April 2021 has shown a development in that direction. But there must be a deadline. If Senior General Min Aung Hlaing continues to allow the military to act brutally against the Myanmar people who oppose the power took over, ASEAN must act decisively, for instance, temporarily suspending Myanmar’s membership in ASEAN with all the consequences, including General Min Aung Hlaing may getting closer to China which in fact a few days ago supplied huge investment funds to the Myanmar government when the world community criticized the Myanmar government.

A group of uniformed schoolteachers protesting in Hpa-an on 9 February, 2021. Wikipedia Commons

South China Sea

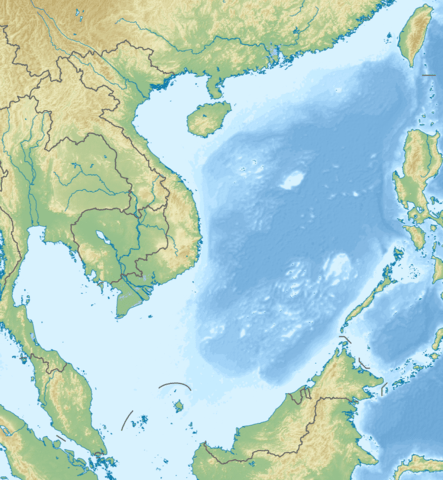

The South China Sea (SCS) area includes the waters and lands of an archipelago of two large islands, namely the Spratlys and Paracels, as well as the banks of the Macclesfield River and Scarborough Reef which stretch from Singapore, starting from the Malacca Strait to the Taiwan Strait. Because of this vast expanse of territory, and the history of successive domination by traditional rulers of nearby countries, today, several countries, such as the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Brunei Darussalam, are involved in confrontational attempts to claim each other, over part or all of the said territorial waters.

South China Sea. Wikipedia Commons

However, the problem became very serious after the PRC’s absolute claim to the waters of the SCS emerged in 2012. This in itself has raised concerns in surrounding claimant and non-claiming countries, as well as countries outside the region over the future of control, stability and security of the territorial waters there. The increasing concern has then triggered an escalation of tensions, as a result of military maneuvers and efforts to show each other’s strength and provocation and intimidation in the water and the diplomatic arena. Furthermore, aggressive behavior and several provocation efforts were carried out by the PRC navy in the SCS, which they claimed absolutely, against the navy and fishermen from the Philippines and Vietnam, or vice versa.

This also threatens Indonesia’s sovereignty and interests in the Natuna waters, which is part of the Riau Archipelago Province. With this absolute claim, not only Indonesia’s territorial sovereignty over the Natuna Islands is threatened, but also all of Indonesia’s interests as an archipelagic country based on the Archipelago Insight concept, whose existence is respected based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1982, in particular management rights for the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) up to 200 nautical miles. In fact, without this alone, the traditional rights of Indonesian fishermen around the waters of the Natuna Islands are already threatened.

The case of the SCS has shown the fragility of ASEAN because there is no cohesiveness among ASEAN countries in responding to China’s actions. When the International Court of Justice in 2016 ruled that China’s self-developed Nine-Dash Line (which shows that 80 percent of the SCS including parts of the Philippines and Vietnam are Chinese territory) is illegal and the division of the SCS area must be in accordance with international agreements (UNCLOS 1982), and China rejected it, other ASEAN countries did not defend the Philippines or speak out against China.

The reason as ASEAN stated is that in order to maintain peace, the SCS issue should be resolved diplomatically. Indeed, this method is highly desirable. However, if the Chinese government stubbornly refuses to comply with the International Court of Justice’s decision, it is time for ASEAN to choose a tougher approach. As Flavius Vegetius Renatus said around 400 AD “Qui desiderat pacem, bellum praeparat”, which means “Who wants peace, prepare for war”, ASEAN must be ready for war not in the true sense but to act more decisively, including by reviewing or temporarily canceling existing agreements between ASEAN and China. ASEAN must be aware that the longer this affair drags on, the stronger China will be in the SCS. Because there is no sign that the Chinese government will stop building its military infrastructure in the disputed area.

It is indeed very difficult to get ASEAN cohesiveness when dealing with China. Because there are some ASEAN member countries whose economies are highly dependent on investment from China, especially Lao PDR, Cambodia and Myanmar. Maybe if asked to choose China over ASEAN as the source of their economic growth, the three countries will say China! So, one of the serious challenges facing ASEAN is that how all member countries feel that the existence of this regional organization is really useful, especially in the economic field.

Bandung Principle in Question

These issues of Myanmar Political Crisis and SCS are also very relevant to be discussed in the relation to the “Bandung Principle” on sovereignty and non-interference. Indeed, sovereignty and non-interference are what all countries want and strive for, including countries that were actively involved in the Asia Africa Conference in 1955, including China and Indonesia. However, life in this world is not constant but very dynamic which really requires appropriate adjustments, including in the procedures for economic, social and political relations between countries, regulations, laws, and principles.

The Merdeka Building, the main venue in 1955 for the first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference—also known as the Bandung Conference, a meeting of states, most of which were newly independent, which took place in Bandung, West Java, Indonesia.

The question now is not whether the Bandung Principles need to be completely changed. Certainly not. However, the following two questions need to be discussed in the Bandung Spirit movement, namely:

-

- to what extent or under what conditions should a country not intervene in another country?

- if intervention is needed, in what form is it appropriate?

That first question is very relevant now. Remember, for example, the 1999 Bosnian War. Was it wrong or do we regret that NATO, EU and UN have intervened which ultimately ended the war? Will the international community have to remain silent if the Taliban who are currently in power in Afghanistan repeat their pre-2021 behavior which did not respect women’s rights and tortured their ideological opponents?

The second question is very important because there are two forms of intervention, namely ‘hard intervention’ such as the US attack on Afghanistan in 2001 and ‘soft intervention’ such as the meeting between Senior General Min Aung Hlaing from Myanmar with other ASEAN leaders in April 2021 which was initiated by Indonesia. Another example, Indonesia managed to get back Irian (now Papua) from the Netherlands, not through a big battle but through a soft intervention by President J.F. Kennedy who urged the Dutch to withdraw. Increasingly complicated world problems ranging from global warming, environmental damage, international refugees, pandemics such as Covid-19, to civil wars or conflicts in a number of countries make absolutely no-intervention impossible. Whether a soft or hard intervention is chosen depends on the conditions at that time and changes after the intervention was carried out. When Iraq attacked Kuwait in 1990 the international community began with a soft intervention by pleading with Saddam Hussein to withdraw his troops from Kuwait. But there was no change in Saddam’s attitude, so in the end the US and its allies made a hard intervention.

So, as a final word, how the Bandung Spirit movement with its Bandung Principles responds to changes in an increasingly complex world is our homework.

Tulus T. H. Tambunan

Center for Industry, SME and Business Competition Studies, Universitas Trisakti, Indonesia